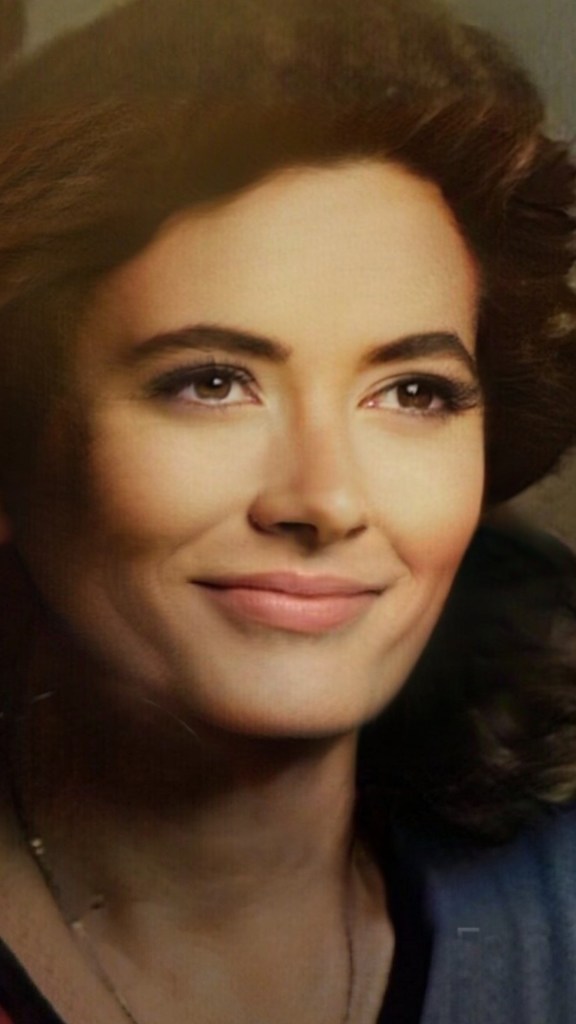

Gabriella Balcom lives in Texas with her family, works full-time in the mental health field, and has loved reading and writing her entire life. She writes fantasy, horror, sci-fi, romance, literary fiction, children’s stories, and more, and loves great stories, forests, mountains, and back roads. She has a weakness for lasagna, garlic bread, tacos, cheese, and chocolate, and adores Chinese, Italian, and Mexican food. Gabriella has had 444 works accepted for publication, and won the right to have a novel published by Clarendon House Publications when one of her short stories was voted best in an anthology. Her book, On the Wings of Ideas, came out afterward. She was nominated for the Washington Science Fiction Association’s Small Press Award, and won second place in JayZoMon/Dark Myth Company’s 2020 Open Contract Challenge (around one hundred authors competed for cash prizes and publishing contracts). Gabriella’s novelette, Worth Waiting For, was then released. She self-published a novelette, Free’s Tale: No Home at Christmas-time, and Black Hare Press published her sci-fi novella, The Return, in 2021. Dark Myth Publishing released her Down with the Sickness and Other Chilling Tales in November 2022. Others pend publication. Her Facebook author page: https://m.facebook.com/GabriellaBalcom.lonestarauthor

I Don’t Want To

Cami sniffled, tears welling up in her big brown eyes and rolling down her cheeks.

“Don’t cry, honey,” Lana murmured, gently dabbing Cami’s face. “Go ahead and eat your banana. You love bananas.”

Once the girl began chewing, Lana marched into the living room. “How could you?” she whispered fiercely.

Bernice reached for the ham-and-cheese sandwich lying beside her on the couch, but Lana snatched the plate away before she could get it. “This isn’t yours, and you know it. You already ate your food.”

“It wasn’t enough,” Bernice retorted.

“You could’ve made more.” Lana carried the sandwich into the kitchen, set it in front of Cami, and returned to stare at Bernice.

“You always give the kids extra,” she complained. “But you hardly feed me anything at all.”

“How can you say such a thing? You had two sandwiches, plus fruit, chips, and cookies. I made Max and Cami just one sandwich apiece.”

Hours later, Bernice sulked. “I don’t want to,” she grumped. “My show’s about to come on.”

“You’ve been watching TV for hours, and it won’t kill you to stop for a few minutes.” Lana replied. “All I asked you to do was sweep the kitchen and take out one bag of trash.”

“Have the kids do it.”

“They already did their chores.”

“You do it then.”

“No. I worked all day while you relaxed at home. I fixed food here even though my arthritis is acting up. And I cleaned out the fridge and did laundry, too. You need to do your share now.”

Bernice narrowed her eyes. “You’ve always favored those brats over me.”

Lana studied her daughter with haunted eyes. “Don’t start that again. You say it every time I ask you to do anything.” She rubbed her back, then her right knee, wincing as she gingerly lowered herself into a recliner. “I love you and I’ve shown that a million times over regardless of your behavior. You’re a grown woman, for heaven’s sake. Twenty-seven years old, healthy, and capable. The kids are three and five. And they’re your children.”

“They’re a pain in the ass.”

“No, they’re not.”

“Cami’s nothing but a whiner.” Bernice’s lip curled.

“She cried earlier because she was hungry. You ran off with her food, remember? And how could you do that, anyway? You just walked away like — like…” Bernice began a game on her phone. Realizing she was being ignored, Lana frowned. “Doing that while I’m talking to you is rude.”

Her daughter raised her head, but only to sneer.

“You were supposed to feed Cami and Max when the babysitter dropped them off,” Lana said. “I had to work late. It wasn’t fair to keep them waiting till I got here.”

“I never wanted them.” Bernice’s voice was glacier-cold.

“Then you should’ve used birth control,” her mother snapped. “Thank goodness they’re in bed and not hearing this.”

The younger woman shrugged.

“I’ve been raising them since they were born.” Lana’s voice cracked. “You ignored them. You wouldn’t feed them. Wouldn’t change them. Did nothing when they cried. I had to push you to do anything.” Her daughter didn’t show any sign of having heard her words, and she sighed, changing the subject. “Rent, utilities, and food aren’t free. They cost, and prices are constantly going up. The last few weeks, I’ve repeatedly asked you to get a job to help with expenses.”

“I got one.”

“You were fired within days.”

“So? I don’t want to work.”

“I’d love it if I didn’t have to work, but I’m not rich. I’m fifty-nine and only have a few workable years left, especially if my arthritis worsens. When I do retire, I won’t get much Social Security because I haven’t made a lot.”

“You can get food stamps for us. And money from the church. Lots of other places in town give people stuff, too.”

“I don’t want welfare or handouts because I’m capable of working. So are you.”

Two days later

“Shut up!” Bernice yelled at the kids.

Lana glared at her, then ushered Max and Cami outside to the waiting van. A church friend had invited the children to her son’s birthday party, offering to pick them up and bring them home later.

“Those spoiled brats are always blabbing and wanting something,” Bernice griped.

“In case you’ve forgotten, you also ask for stuff. I stand all day long at work and my feet hurt when I get home. That’s why I was soaking them. And you saw what I was doing — I’m sure of it. But you wanted me to make you toast, hand you an apple, paper towels, and other things just so you wouldn’t have to get up yourself.”

“You got the kids more beef stroganoff when they asked.”

“Yeah, because they’re little. If they’d tried to get it themselves, they could’ve been burned or knocked the pot off the stove or something. You’re capable of making yourself sandwiches, opening cans, heating stuff…”

“Shh. I can’t hear the movie.”

Lana sighed. “The laundry is still heaped up in the hallway and the dishes are still in the sink. You were supposed to take care of both.”

“I’m not your slave. I shouldn’t have to clean up after everyone.”

“The laundry and dishes weren’t left there by other people. They’re yours. I do meals every day. You refuse, even if your kids are hungry. All I ask you to do is vacuum three times a week, take the trash out now and then, and occasionally clean the tub and toilet. And, you’re responsible for your own laundry and dishes.”

“The kids should do more.”

“Max helps with dishes as much as he can, and he and Cami wipe the table. Max sweeps, vacuums, and takes trash out, and they help me with laundry. What they do isn’t perfect, but they try. They’ve learned to put their dirty clothes in the baskets I put out, but yours are strewn around your room and bathroom.”

“Who cares?”

“Bending and picking things up hurts me. I shouldn’t have to. Putting stuff in baskets isn’t hard.”

Bernice shrugged.

Lana took a deep breath. “Your attitude really bothers me. No matter how many times I talk to you, nothing changes. When I told you why I was soaking my feet earlier, you didn’t care. Asking me to do more when I’m hurting isn’t right. I’m tired. You’d been home and could’ve easily…” Lana trailed off when Bernice raised the TV volume. “I’ve said this so many times; I don’t know why I bother. You can’t go through life waiting for people to serve you, while you sit around and do nothing.”

“You cater to the spoiled brats.”

“They’re not spoiled brats.”

“You blame me for everything.”

“No, I don’t.” Lana’s head throbbed. “I hold you accountable for yourself. I don’t understand why you won’t help. You show a total lack of caring.”

Turning cold eyes on her mother, Bernice asked, “Why would I care about any of you?”

Lana’s stomach churned. “You watch shows, play on your phone, and help yourself to food my hard work provides. You never clean up, never help anyone. I have to say something a hundred times to get you to do the smallest thing. You leave your dirty dishes everywhere, and you aren’t putting a cent toward bills. And, don’t think I’ve forgotten how you treated me.”

Bernice widened her eyes, but their expression remained hard and uncaring. “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Yes, you do. Last week, I was sick with a high fever, vomiting, and diarrhea. I could barely stand without doubling over in pain, but the kids were hungry. I forced myself out of bed when you wouldn’t help, but I was dizzy and fell in the hallway. You saw me there. I was weak. Hurting all over. I asked you for help, but you wouldn’t. Thank goodness I finally managed to get up. Then, after I warmed up leftover spaghetti for the kids, you took off with Max’s bowl. What kind of mother takes her child’s food?”

“I was hungry.” Bernice snorted. “Of course he tattled. Lousy whiner.”

“He didn’t tattle. I saw you. But that’s not the point.”

“Point? You never have one. You’re a boring old dumb-ass, nagging all the time.”

Lana flinched as if she’d been struck. Paling, tears sprung to her eyes. “You care about no one but yourself, and I have nothing left to say to you. You have till the end of the week to be out of my home.”

***

two weeks later

“I hate her,” Bernice growled, voice ringing with resentment.

“Young lady, that’s enough,” Hildy replied. “That’s your mother and my child. She’s put up with a lot from you, and you know it.”

“Bullshit. She’s nothing but a mean bitch.”

Hildy gasped. “Don’t use that kind of language. And why would you say horrible things like that? She raised you and helped you all these years. Asking you to do chores was fair. She has your kids learning to take responsibility and help, too. There’s nothing wrong with that.”

“Stupid kids.”

“They’re not stupid, and you got pregnant with them, not your mama. She didn’t have to help but she did because she’s a good woman. She could’ve put you out. The kids also, since they’re your responsibility.”

“I would’ve dumped them first chance I got.”

Hildy’s mouth dropped. “You carried them in your belly. Don’t you care about them?”

Her granddaughter stared at her, eyes cold. “No.”

“You can’t mean that.” Hildy moved, standing between Beatrice and the television.

“Get the hell outta my way!”

“Don’t you ever talk to me that way. It’s rude and disrespectful. Apologize.”

Bernice muttered something under her breath.

“What?”

“So—oo—ry,” Bernice said, drawing the word out. She added, “Bitch,” after her grandmother walked away.

Four days later

“Today’s Thursday,” Hildy commented. “Your dishes from the week are still in the sink. Grab the ones beside you and go wash them.”

“I don’t want to. You do them.”

“I didn’t dirty them. You did.”

Three days later

“The dishes still aren’t washed,” Hildy stressed. “Your Mama and kids are coming over tonight. I want the house to look nice.”

“Why are they coming?”

“To visit. You haven’t seen them since moving in. Don’t you miss your children and want to do stuff with them? Hug them?”

Bernice stared blankly at Hildy.

That evening, Max and Cami raced back and forth, playing tag. They periodically stopped to play Chutes and Ladders with Hildy and Lana. Although Bernice sat across from the children at the kitchen table during dinner, she hadn’t said anything to them since their arrival. They didn’t seem to notice.

Cami ran from her brother, giggling, and paused in front of Bernice, blocking her view of the television.

“Get outta my way!” Bernice leaned forward and shoved the child hard.

Losing her balance, Cami fell against the coffee table, bumping her forehead before landing on the floor. She wailed, scrunching up her nose and holding her head.

“Bernice!” Hildy snapped, kneeling to gather the child in her arms.

Lana bit her lip, exchanging a glance with Hildy.

Max backed away from his biological mother, eyes shadowed by fear.

***

“May I have a word with you, Bernice?” Lana struggled to keep her voice calm. Her daughter ignored her. “Step into the hallway with me. Now.”

“Go with your mother,” Hildy added.

In the hall, Lana studied her daughter. “That wasn’t right.”

“She got in my way.”

“It wasn’t deliberate. She was playing. And you could’ve asked her to move instead of pushing her.”

Lana’s words had no effect. Her chastisement didn’t either. The offender returned to the living room, dropped onto the couch, and turned up the volume on the TV.

***

Three weeks later

“I’ve been talking about missing plates and silverware for days now,” Hildy said. “Why didn’t you tell me they were in your room?”

Bernice didn’t respond.

“You could’ve put them in the sink instead of leaving them out,” her grandmother continued. “I’ve had roaches before and the nasty creepy-crawlers were hard to get rid of. Food attracts them and other critters. You know that.”

“If you don’t like things being out, go pick them up.”

“You pick them up. And dishes and leftovers aren’t the only problems in your room. It stinks to high heaven. There are rotten banana peels and apple cores everywhere. Watermelon rinds and heaven knows what else. Towels are piled up. Some must’ve been damp, because mold is growing. The same thing’s happening with your clothes.”

“I need new stuff.”

“No. You need to take care of what you have, wash it, and not leave it lying around for weeks.” Noticing Bernice’s attention was directed at the TV, Hildy turned it off. “It’s high time you got a job. We agreed you’d work and help out.”

“I don’t want to work.”

“Well, I’d like to be a fairy princess with a castle and a genie to grant me wishes.”

“You’ve got money.”

“I get Social Security. Nine-hundred-forty-seven dollars a month. That’s barely enough for my expenses, and you’re here now.”

“I got a job.”

“You didn’t go in on your second day and they fired you. The job before that — the manager called me, wondering if you were mentally ill. She said you stood around and did nothing.”

Bernice walked away.

“I don’t understand why you act this way,” Hildy said, following the younger woman into her room.

Lying on her bed, Bernice began fiddling with her cell.

Hildy frowned. “Did you hear me?”

“Huh?”

Four weeks later

“You ruined them,” Hildy said, voice rising. “One was my mother’s.”

“What are you talking about?” Bernice leaned to her right, trying to see the television around her grandmother.

“My towels. I had to throw all but one away. I asked you to wash them weeks ago. When more and more vanished, you said you didn’t know where they were, but I just found them. Stuffing them in a trash bag and hiding it in the shed is not doing laundry.”

“Buy more.”

“I can’t afford to. Why did…”

“Shut up, you whiny, old bag.”

Hildy gasped, her face paling. “Don’t talk to me that way.”

***

A week later

Bernice finished the banana, slinging the peel across the room. She ate all her sandwich but the crust, dropping it on the floor. After eating the chips and cookies on her plate, she slid it under her bed.

“Bring me more cookies,” she yelled. Silence was her only answer, and she remembered Hildy had been rushed to the hospital with chest pain.

Once she’d searched the refrigerator and cupboards, Bernice groaned. There was food, but none of it appealed to her, and she had no intentions of cooking.

After ransacking Hildy’s room, she found an envelope labeled “Water Bill” with $40 inside. She took the money and ordered pizza.

An hour later, she tossed the half-empty pizza box into a corner.

She bathed, then dropped her wet towel on top of the box. Since she didn’t have anything clean, she went through a pile of dirty clothes on the floor, searching for something to wear.

Relaxing in front of the living room television, she heard a scraping noise and flinched, looking around for the source. She saw nothing. However, a pair of dirty jeans she didn’t remember taking off lay on the floor.

With a shrug, she focused on her movie.

Something grabbed Bernice’s foot moments later and she squealed. Her eyes widened when she saw the sleeve of one of her shirts wrapped around her ankle. Leggings inched across the floor toward her, winding themselves around her other ankle.

The clothing yanked her off the couch, and dragged her down the hall. She yelled, flailing around, grabbing for doorways and walls, trying to get free.

In her room, her shoes and bedding rose in the air. They hovered for a few seconds before swirling around in a frenzied tornado, picking up her other possessions in the whirlwind. A plate sailed toward her, eyes and a twisted mouth appearing on the surface. Maniacal laughter emanated from it.

“Help!” Bernice yelled.

A pair of sweats rose into the air, soared over to stop in front of her, then floated to the ground, standing upright. One leg grabbed her right arm.

“Let go!” She struggled to get out of its grip.

“I don’t want to,” a voice replied, seeming to come from the sweatpants.

“We don’t want to either,” other voices called out.

Rotten banana peels soared toward Bernice. She tried to dodge them from where she lay, but they struck her right arm before dropping to the floor. The places the peels struck her tingled and shimmered. Bernice screamed as her arm began shrinking, turning a dirty brownish-yellow. Within a matter of seconds, a rotten peel hung from her shoulder instead of her arm. Dry and shriveled, it turned almost totally black, and broke off.

Apple cores hit her left shoulder, which started to change, morphing into a mushy, brown rotten apple.

She blinked in disbelief, crying and bellowing for help. Plates tapped her right leg, which took on a white, porcelain sheen before growing smaller, turning into two saucers.

No longer being pinned down, Bernice hopped frantically toward the doorway, but the clothing that originally dragged her there raced after her. Winding themselves around her remaining limb, they transformed it into dirty jeans.

With nothing left to support her torso, Bernice toppled over, landing with an oomph.

“Why are you doing this?” she wailed, sitting up on her elbows. “Go away and leave me alone.”

“We don’t want to.”

Everything circled her, repeating the phrase again and again.

The discarded pizza box slid toward Bernice on one of its sides. It toppled onto her chest, which slowly took on a flat, brown appearance. Soon, several pizza boxes lay where her torso had been.

Discarded underwear dropped onto the helpless woman’s head, transforming it into stained panties as she yelled.

Only Bernice’s eyes and mouth remained, and she continued screaming hoarsely — all she could manage now.

A wadded Kleenex she’d blown her nose on weeks before floated over, dropping onto one of her eyes, turning it into a second crumpled tissue.

Old, partially eaten pieces of bread landed on her second eye and mouth — even as a prolonged wail rose from it — and they both elongated into dried bread crusts.

Everything floating through the air returned to their previous positions, immediately becoming immobile once more. Bernice’s room looked exactly as it had before, with the exception of a few more discarded items lying here and there.

The end.