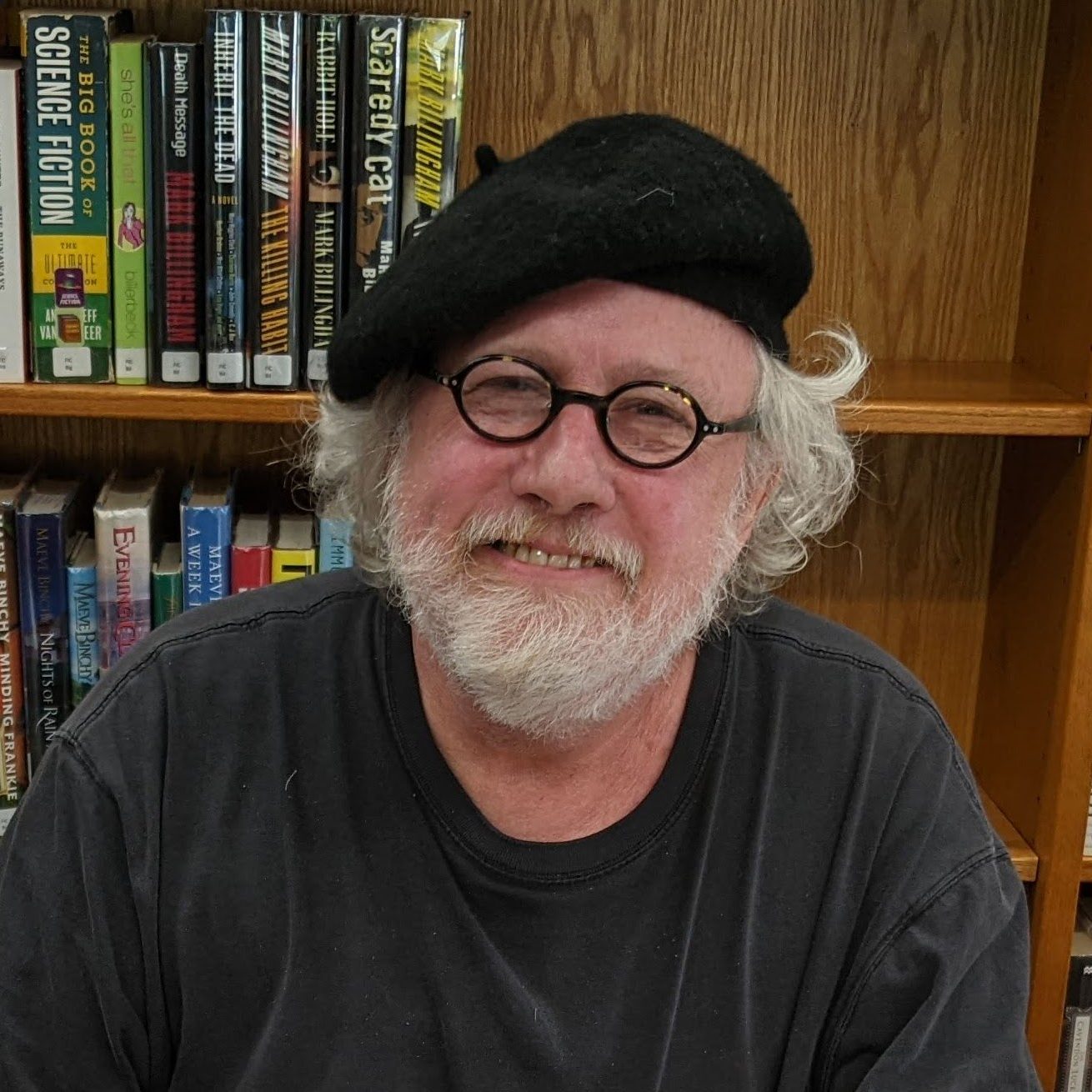

Charlie Brice won the 2020 Field Guide Poetry Magazine Poetry Contest and placed third in the 2021 Allen Ginsberg Poetry Prize. His sixth full-length poetry collection is Miracles That Keep Me Going (WordTech Editions, 2023). His poetry has been nominated three times for the Best of Net Anthology and the Pushcart Prize and has appeared in Atlanta Review, The Honest Ulsterman, Ibbetson Street, Impspired Magazine, Chiron Review, The Paterson Literary Review, and The MacGuffin (forthcoming).

Raise Your Glasses

Raise your glasses to George, our up-and-coming history professor, sure to be, one day, the chair of the department, and to his gorgeous and charming bride, Martha, daughter of our esteemed university president. Grant them the joys and bounty of married love. On such an auspicious occasion we would never mention how much George despises working for Martha’s father who, to him, resembles a fat red-eyed mouse, nor could we foretell that he would, at a faculty party, bully George into donning boxing gloves and entering a ring with sweet Martha, who will knock him cold in front of his colleagues. No, we’re here to wish them marital bliss. There will be no chance that George will remain an unambitious milquetoast and that Martha will develop a wandering eye, viciously flirt with, and occasionally bed, his colleagues. Again, we wish to celebrate the nuptials of this promising pair as they embark on life’s journey together. We wouldn’t even hint at the crushing impact their failure to produce a child will have on their relationship, or how infertility will propel them into endless evenings of drunken soliloquies delivered to each other and their unsuspecting guests, hate-filled hours where they’ll try to destroy themselves and those around them. We won’t describe how Martha’s booze-breath befouls their bedroom and how George is flabbergasted at his flaccid fate. No, this is a hope-filled occasion, unsullied by games like Hump the Hostess or Get the Guests. We wish them the brightest best for their love, love that George will give Martha to make her feel safe, and that she will despise, dilute in infidelities, but fail to destroy. Lest we forget, we raise a glass to their little bugger, the child whose being depended on their hate, the boy who held them together during their bloody battles and bouts of bickering, who laughed hysterically when daddy called mommy a sub-human yowling monster and claimed that she was her father’s right testicle; who couldn’t control his guffaws when mommy called daddy a zero, a great big fat flop, and threw herself at men half her age. We raise a glass to their blond-eyed, blue-haired son, even though he was only a figment of their tear-filled imaginations—tears they poured into ice trays and hid in their freezer. Finally, we wish young George and Martha, star-crossed and fresh as the fragrance of sulphur, all happiness as they fade into the woodwork of existence and slip into the mausoleum of the everyday.

I Wanted In

First, I had to lose weight. Jack, Sean, and Phil were cool. The girls swooned and fans cheered when one of them made a layup or caught a pass. They were the trinity. I was the fat boy who played drums in the marching band—weighed 164 pounds in 7th grade. My plan? One meal a day. A Lucky Strike and a cup of Folgers for breakfast, a walk down Central Avenue to Penny’s record store to buy the latest Beattle 45 for lunch, anything the Swanson company or my mother could whip-up for dinner. The weight just rolled off. Those husky-sized pants mother bought for me luffed in Wyoming wind, looked like deflated camp tents hanging off my legs. Jack noticed the difference, helped me pick out skin-tight black jeans at Fowlers Clothes, found suede Beattle boots and a lapel-less jacket at Waldman’s on Carey Ave. So vested, I sat for hours behind my cheap gold-spackled Japanese drum kit with cymbals that sounded like garbage can lids—dreamed I was Ringo Starr. My hair, I proclaimed, would grow as long as John Lennon’s. That’s what you think, my father said, but died soon thereafter. The girl I fell for was more interested in arm-wrestling the football team than smooching with me on my basement couch. BTW she usually won. Father-death and unrequited love, my weight loss regime, broke the triangle, made it a quartet—me, Sean, Jack, and Phil. That road, long and winding, ended long ago. Phil dead at 50, Jack old and alone, Sean replaying his glory days in a terminal loop. Some claim that only a thin membrane separates us from a parallel universe. Perhaps that membrane is memory—a vaporous inscape where a boy’s wish to fit in resides within a slim scrim called the past.

Go in Peace

Go in Peace the priest admonishes at the end of Sunday mass. He might as well have intoned: Boogity! Boogity! Boogity! Let’s go racin’ boys! Hands dripping with holy water, the Faithful squeeze, elbow, their way out the front door and into the parking lot behind St. Mary’s Cathedral. Who can get home first to see the Game of the Week, place the sirloin tip into the roaster, and pop the top of the first Bud or Coors of the day? My sweet mother, blessed behind the wheel of her big fat baby blue Cadillac, cut-off in the parking lot by a satanic sinner in a jeep, rolls down her window and yells, You son-of-bitch! The profligate in the jeep uses a hand signal to indicate that he’s only moving one mile an hour and exhorts, Go to hell! Engines roar, tires spin, dust clouds reach toward heaven under the cruel July Cheyenne sun. In 1959 we don’t understand the prophesy, the prescient warning, of what’s to come: the crimson mist above JFK’s head in Dallas, MLK’s shoes lifeless on a motel patio in Memphis, RFK’s blood-puddle on a kitchen floor in LA, helicopter whoops over rice paddies in Vietnam, bombs cratering villages in Iraq and Afghanistan where dust permeates everything—food, tents, the barrels of M-4s—panicked evacuations of allies and troops in Vietnam and Iraq. We didn’t see the promise of that hate-filled parking lot where the devout frenzied like barbarians at a martyr’s barbecue. Go in peace, the priest said.