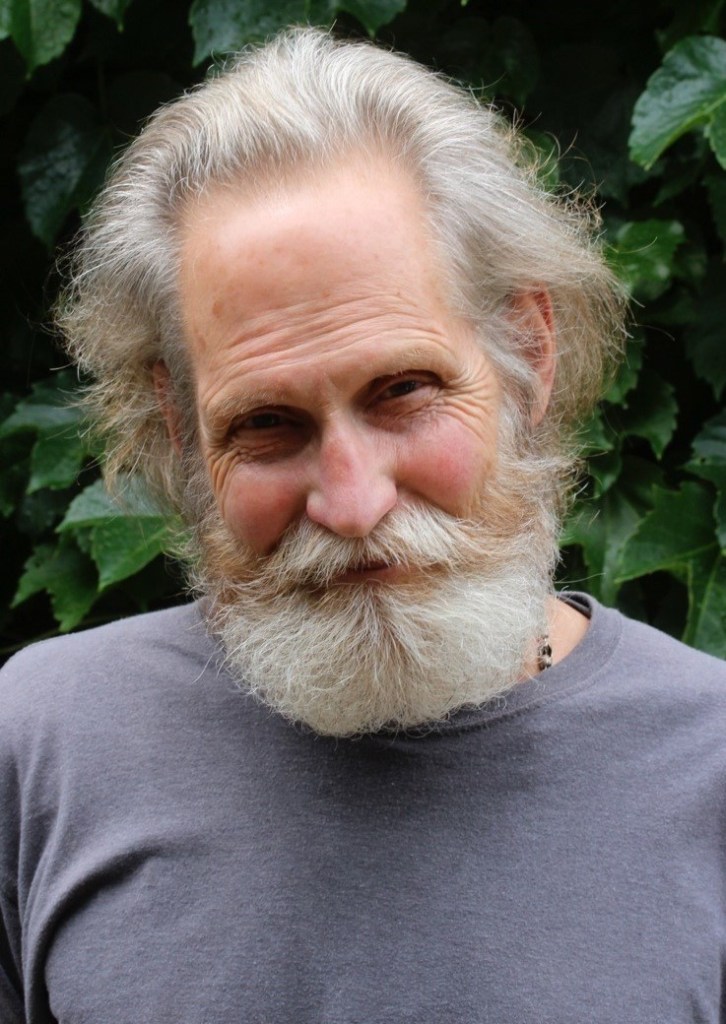

Jim lives in a small town twenty miles west of Minneapolis, Minnesota. His stories and poems have appeared in over two-hundred online and print publications. His short story “Aliens” has been nominated by The Zodiac Press for the 2021 Pushcart Prize. His collection of short stories Resilience is scheduled to be published in early 2021 by Bridge House Publishing and Short Stuff a collection of his flash fiction and drabbles will be published by Chapeltown books in 2021. In addition, Something Better, a dystopian adventure, will be published by Paper Djinn Press in early 2021. All of his stories can be found on his blog: www.theviewfromlonglake.wordpress.com.

The Visit

I sat in the visitor’s room and tried without much success to control my breathing. My heart was racing and I was on the verge of hyperventilating. Get a grip, I told myself. It was about ten degrees outside in the middle of January so why did it all of a sudden feel like a hundred degrees in here? Sweat was running down my sides under my flannel shirt like a river.

I was in cheap plywood sided cubicle painted dark green, one of maybe a half dozen others along the row. Mine was the only one occupied. A thick pane of glass separated me from the other side, the side where my older brother now sat. The brother who I barely remembered. The brother who was serving a life sentence for murder.

My senses were super charged, probably caused by the adrenaline raging through my veins like a flash flood. The florescent lights were yellowish blue and too bright. I took off my glasses and rubbed my eyes to give them some relief but it didn’t help. I put them back on. My nerves were on edge so I held my hands together in my lap to keep them from twitching. The room smelled of lemony chlorine disinfectant, and there was a hint of stale body order mixed in. Not the kind of scent you’d find in an artisan bag of potpourri that was for sure.

There was a low rumbling din of mechanical noise in the background making me wonder what it must be like to live in a place like this where there was never complete silence. As a person who occasionally drove to the country just to hear nothing but the sounds of nature, I think I’d go nuts in about a day if I had to be incarcerated.

Speaking of which, nervous as I was, I made myself look at my brother. He was a huge man, probably six feet four and at least two hundred and sixty pounds with muscles bulging out of his tight black tee-shirt that said Have a Nice Day on it. His head was shaved and he wore about a foot-long Billy-goat bead that was pure white. His dark brown eyes were deep and penetrating and his fingers on his right hand were stained yellowish orange with nicotine. To be honest, even though he was my brother, he still looked like the murderer he was.

Zach was twenty-one and I was five when he shot and killed a husband and his wife and their two small children on a failed robbery attempt out in rural Wright County, an hour west of Minneapolis where we grew up and I still live. He was high on amphetamines at the time and still tearing the farmhouse apart looking for money when the highway patrol, sheriff’s department and local police showed up, fifteen law enforcement officers in all. The neighbors had called it in, having heard the barrage of gun fire coming from the Atkinson’s family’s farm. The poor people were surprised in their sleep and never stood a chance is what everyone said.

The trial was short. My brother was sentenced to life without parole and sent to serve his time in North Dakota at the maximum-security prison in Dickenson, a six-hour drive from Minneapolis.

I knew nothing about Zach’s crime. He was so much older than me that if what happened did register in my five-year-old brain it certainly didn’t stick. And it was never talked about afterward, either. The murder and the trail ruined my parent’s marriage, and Dad left the next year taking my next oldest brother Paul with him. I never saw either of them again. Mom told me that they moved to Alaska and wanted to be left alone. There was a lot of bitterness between Mom and Dad, I guess. I was still young and never close to Paul, so I didn’t really care one way or the other.

Mom got on with her life and raised me and my younger sister, Savannah, and as far as I’m concerned did a great job. We moved from our small rambler in the suburb of Richfield to a tidy two-bedroom apartment in south Minneapolis near a park. Mom worked at a nearby big-box store, didn’t drink much or smoke too much, and made sure the bills were paid on time.

I was quiet and withdrawn and a passably mediocre student. I compensated for being occasionally lonely by playing video games. To this day, I still love them.

I moved out after I graduated from high school and started working full-time for Clean-Rite cleaning services. I found an apartment within walking distance from Mom. We visited and had coffee at least three times a week and talked on the phone every day. We were very close.

But she never told me about my brother, the murderer. Not until she was dying, that was.

“Darren, I’ve got something to tell you,” she said toward the end that last day. The cancer had gotten to her bad, and me and Savannah were watching over her along with a nurse and one of the good folks from hospice.

“What is it, Mom?” I pulled my chair up closer to her. We had her bed in the living room of the same apartment where she’d raised us. I considered mom my best friend, so this was hard. I leaned near her ear so she could hear. “Tell me,” I prompted.

She told me, then, about Zach and the murders and the trail and how it affected my dad and how he’d taken Paul and left the state for good and on and on. I have to tell you, I’m not an emotional guy, but even I got a little worked up. Finding out I had a brother, even though he was an infamous murderer, was a little hard to get a handle on.

“Why didn’t you tell me this, before?” I tried to keep my voice down, but, shocked as I was, I’m afraid I might have shouted a little.

Mom smiled a weak smile and said, “I didn’t want to worry you.”

I coughed out a laugh, “What do you mean, worry me?”

“Well, I know how you are.”

She had a point. Maybe it was because I was the oldest after Dad left with Paul, but I did always have what I’d call a bit of the worrier in me. Growing up, I worried about mom, for sure, and how she was doing, making sure she wasn’t working too hard and eating right. I worried about Savannah as she got older, especially when the boys started coming around. And, later, after she moved to St. Paul and got married and had kids, I worried about her and her husband and her family all the time, calling her every other day or so to chat and see how things were going. (If asked, I’m pretty sure she’ll say she didn’t mind then and doesn’t mind now.)

I worried about my job at Clean-Rite and whether or not tomorrow was going to be the day I’d get fired even though I’d worked for them for nearly twenty-five years and was as loyal and reliable an employee of the top-rated building cleaning service company in the metropolitan area that they could ever want. And, there was no reason why I shouldn’t keep working for them for another ten or fifteen years, either. At least. But, still, I worried.

I worried about whether or not I’d ever get married. At forty-four years old and not really interested in even dating, the answer was getting clearer every day: probably not.

I worried if I’d be able to pay my bills. Which I always did, thank you very much!

Stuff like that was what I worried about. So, mom had a point. But I didn’t want that to be her last mortal thought on her death bed. “Mom,” I said, taking her thin hand in mine, “I’m glad you told me about my brother, but please don’t worry. I can handle it.” I tried to sound convincing, and Savannah told me afterward that she thought I did.

“Good,” Mom said, wheezing, out her last breaths. “Because there’s more.”

“More?” No shouting this time. I kept my voice low, thinking, what more could there possibly be? I was about to find out. “What is it, Mom?” I leaned even closer. Savannah pulled her chair next to me and put one hand on my arm and one on Mom’s.

“I want you to go see him,” she whispered. “I want you to go see Zach.”

Those were the last words she spoke. A few minutes later, she inhaled her final breath and passed on. Pretty peacefully, I have to say.

Moments after Mom died, I looked at Savannah and she looked at me. We were both crying but she still had enough in her to say, “Good luck with that last wish of hers, brother. Good luck.”

I knew what she was getting at. She knew because of how close Mom and I were that I’d abide by her final request. Savannah knew me better than Mom in that regard, almost better than myself. And she was right. I was going to have to do what Mom asked of me. It was the way I was made and I made a resolution right there on her death bed: I was going to follow through on Mom’s last request.

***

A tapping on the window between us broke into my thoughts. Zach had his phone in his hand and he pointed it and to mine and made a ‘pick up’ motion.

Oh, right. I needed to get focused on why I was there. The black, scarred phone was attached to a metal cord and hung on the right side of my cubicle. I reached for it, my hand shaking. What was wrong with me? Well, it was obvious. I was going to talk to my brother, a guy who I knew nothing about other than he murdered four innocent people. I have to think anyone in my position would be more than a little freaked out.

I brought the receiver to my mouth, but before I could say anything, Zach said, “Well, well, well, little brother. I got your letter but never thought you’d show up. How was that six-hour drive?”

I was shocked. And speechless, actually. He sounded so…what’s the word? Nice, maybe. Cordial, at least. I don’t know. I was expecting a gruff, smokers voice, grunting out monosyllable words, like the hardened criminals I seen in the movies, but he wasn’t like that at all. His voice was deep and resonant, like that of a person who gave classes on public speaking. He also sounded confident, something I have to say I was not.

My throat was so dry, I covered the receiver and started coughing. I glanced at him from time to time. He just sat waiting patiently for me to finish, a skill I suppose one develops in prison, especially if you’re sentenced to life without parole.

When I finished coughing and was wishing for a drink of water, he said, “So are you going to say anything or are you just going to sit there and cough the whole time?”

Time to get to it. “No. I’m mean, yeah,” I stumbled over my words. Get with it, I told myself, taking a deep breath and admonishing myself to start over. Then I did what Savannah told me to do, and that was to be myself. I said the first thing that came to me.

“Mom died,” I blurted out, watching him carefully. There was no reaction at all, just the stoic expression, I guessed, of one practiced in the art of showing no emotion. So, I went on. “She wanted me to come and meet you.”

He laughed, somewhat sarcastically it seemed to me, “Now why the hell would she want that?”

“I have no idea. Maybe because we’re bothers?”

Zach set the phone down and sat back in his chair. He put his muscular arms up and locked his hands behind his head and starred at me, giving me the distinct impression he was assessing my statement. His arms were covered in tattoos. I couldn’t make out anything specific, but I will say this, with the tattoos and the shaved head and the long beard, he was one of the most intimidating looking guys I’d ever seen.

Finally, he picked up the phone and said, “So you didn’t know anything about me?”

“No.” I wiped some sweat off my forehead. “I mean I now know about the mur…the killings,” I said. “I read up on them online.” He nodded. “I read about your trail and all that.” He nodded some more. “I know about your sentence.”

His eyes softened. He leaned forward, picked up the phone asked, “You don’t remember anything about us as kids?”

“No. Not a thing.” Then added for some reason. “Sorry.”

He yelled into the phone, “Sorry! You’re sorry?”

“Well, yeah.” I was thrown off. Why was he so mad?

“You don’t remember me or what happened or the trail or anything? Nothing?”

“No. Like I said, I was just a kid,” I said, and added, again, “Sorry.”

He leaned close to the glass. I could see his teeth which were remarkably white. “Quit saying that. You’ve got nothing to be sorry about, okay? Like you said, you were just a kid.”

I nodded my head. “Okay,” and had to bite off the urge to say “sorry” again. That seemed to satisfy him.

One thing was certain, there was a lot of rage there. An awful lot. But I have to say, I was enjoying being with him. When Dad left with Paul, I was only seven, so having a brother to talk with was pretty nice, and even though he was a convicted murderer it was not as bad as I thought it was going to be. I felt a connection with him somehow. Some kind of genetic thing, I guess. It didn’t feel all that bad.

We were quiet for a minute or two before he asked, “So what do you do?”

I told him about my job at the cleaning services company, Clean-Rite. “I’ve been there for almost twenty-five years.”

He laughed. “We’ve got something in common. I work in the laundry. Been doing it since I got here.” He paused and went on, “What else you do? Like for fun?”

“I play video games. I’m in some online groups. It’s fun. How about you? Do you play?”

“No. I kind of shy away from anything that’s got violence associated with it.” Seemed like a good idea to me, but I didn’t say anything, just nodded my head as he continued. “I take online classes. I’ve gotten a BA in Sociology from the University of Minnesota. I do some counseling here in the prison. I read.” He laughed, “You’ll never believe it, but I write poetry and send it out. Some of it’s been published.” He shrugged his shoulders, “I work out.” He looked off into the distance. “I try to stay busy.”

I listened to him and hoped my mouth wasn’t hanging open too much. I couldn’t help comparing how Zach spent his time to mine. He was confined in prison yet living a rich and rewarding life, and I was kind of doing the opposite, going to work and playing video games and not much else. I didn’t even talk to anyone all that often, especially now that mom was gone, just Savannah occasionally, but she had her own life with her job and husband and kids and everything.

“I miss Mom,” I suddenly blurted out. “I miss her a lot.”

He stared at me, “You know you and I were close once, don’t you?”

Why had he changed the subject? “Ah, no, I didn’t know that.”

“I used to take you fishing at the pond by where we lived. I used to buck you on the back of my bicycle and take you bike riding. We built model airplanes together. We were pretty close.”

“What about Paul?” The brother between Zach and me was always a bit of an enigma.

“Paul and Dad were close. That’s all I know. Dad didn’t care much for me or for you, but he and Paul had a thing.” He paused and added, “You said they were in Alaska?”

“Last I knew.”

“Well, I hope they’re happy.”

It seemed there was a lot more there, but I just let it go. Maybe some other time…Wait a minute. Some other time? Would I be coming back?

Zach was suddenly reminiscing. “I remember once you and I were hanging out, walking barefoot along the shore of the pond. It was a hot July morning, and the water felt cool. So did the mud. We were just talking, joking around. You must have been four at the time. We found a frog that you liked. I remember that.” He looked at me. “You remember any of this?”

I racked my brain, but came up with nothing. It was all a blank. “No. Sor…” I caught myself. “No. I didn’t.” Zach smiled at me.

“That’s okay. We walked along for a while and you let the frog go. Then we stepped out of the water to sit on the bank and dry off, but that didn’t happen.”

“Why?” I asked. “What happened?”

“Your feet were covered in leeches like in that movie Stand by Me. Man, you were freaked out. But I took you in my lap and calmed you down and pulled those leeches off one by one. There must have been twenty of them. You were pretty scared.”

Well, I never. I’d had a brother after all. One who liked being with me, maybe even loved me, at least liked me enough to pick those leeches off and spend time with me.

“I kind of remember,” I said.

He laughed. “You liar. You don’t remember a thing, do you?”

“Well… I want to. But, really, no, I don’t.”

He smiled. “That’s okay. I’ve got tons of stories to tell you. If you want to listen.”

Which would mean coming back.

I know what you cynics out there are thinking. ‘The guy is making all this up because he’s lonely and just wants someone to talk to.’ And that’s a plausible thought. But I’m going to disagree, because I want to come back. I like being with him and talking to him.

In fact, that day I made my own resolution: I’m coming back at least once a month to visit with Zach in person. There, I said it. And I’m doing it not because Mom wanted me to, but because I want to. I want to very much. I think there’s a lot I can learn from him in spite of his past. Plus, you know, he’s my brother. And, more than that, I like him. He’s a good guy. He might be the only guy friend I’ll ever have. And, if that’s the way it works out, if that’s what my future holds, then that would be just fine with me. Zach and me. Brothers for life. I like the sound of that.

Great story Jim.

LikeLike