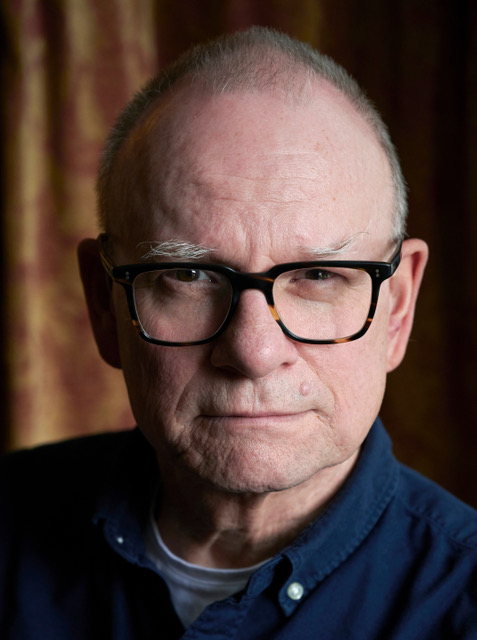

For over thirty years Mike Golding was a photographer and artist, and latterly a lecturer in photography at the University of Northumbria. He retired from academia in 2010 and began writing fiction. He enrolled on the MA in Creative Writing at Newcastle University in 2011, and graduated with a distinction in 2012.

In 2013 he received a New Writing North New Fiction Award for a novel in progress, Salvage, which was completed as A Double Exposure in 2014. And in 2019 he self-published the psychological thriller Bad Magic through Amazon KDP, under the pseudonym A.M. Stirling.

In 2015 he co-founded Wombach Press with fellow graduate Jamie Warde-Aldam. This was a self-funded initiative to help unknown writers find an audience, and published a series of pocket-sized chapbooks of short fiction by four graduates of Newcastle University’s MA in Creative Writing, which were distributed at live readings in the North.

He completed his third novel, Dead Cat Bounce, featuring Tyneside-based private detective Tony Golightly in 2022, and in 2023 his short story ‘Spitfire’ was included in the anthology, Uncommonalities IV, published by Bratum Books.

Flora and Fauna

The woman – early sixties, dyed blonde hair and rimless glasses – stood just inside the doorway of the coffee shop and looked around. She was getting in everyone’s way; people leaving or coming in off the street kept bumping into her.

Robert recognised her from the photograph on the website, although she wasn’t quite as big as he’d imagined. Perhaps it was like seeing someone famous on the street; they never looked the same as they did on television. He pushed himself up from his seat and raised his arm.

‘Marilyn?’

‘Robert?’ She came over, offered her cheek for him to kiss, and dropped down onto the chair opposite his. ‘I can’t face that queue. Get me a skinny latte, would you?’

‘Do you want a piece of cake, or something like that? A pastry?’

‘I’m on a diet,’ she said. ‘Why else would I ask for a skinny latte?’

‘I’m sorry. But you don’t look as if you need to lose weight.’

‘Really? Well, it is a date after all. Get me something with chocolate. I might as well be hung for a sheep as a lamb.’

He came back with the coffee and a wedge of gateau, and she said, ‘You look older than your photograph.’

‘It was the only one I had,’ he said, pushing the plate towards her.

‘You’re not divorced, are you? There’s always something wrong with the divorced ones. Bound to be.’

‘I’m a widower,’ he said.

‘Ah, the widower,’ she said. ‘I’m divorced and I’m straight up about it. But men always lie. I’ve kissed enough frogs to know that. And I’m fed up with it.’ She sighed and cut into the cake with the edge of her fork. ‘Before we start, we need to agree rules.’

‘Rules?’

‘I have three rules,’ she said. ‘One. Don’t ever call me. If I want to get in touch, I’ll call you. You can’t have my number. If you’re not okay with that, let’s call it off now. Okay?’

‘Okay.’

‘Rule number two. We only meet on neutral territory. Until we’re sure. If we are ever going to be sure,’ she said, lifting the fork towards her mouth.

‘Number three,’ he said. ‘What’s rule number three?’

She finished her mouthful of cake, and took a deep breath. ‘Don’t pester me for sex. Men always want sex. It’s all you lot think about, isn’t it?’

He didn’t answer and looked around the coffee shop.

‘These places are all the same, aren’t they?’

She’d called him the week before. From a withheld number.

‘You like art? Your profile says you do.’

‘Oh, yes. Of course.’

Signing up for the dating site had reminded him of filling in application forms when he was looking to go to university. They always wanted to know your interests. It was meant to show you were a well-rounded person. But what was there to put down? Cinema, music, walking, reading; the usual. He’d added cookery to his profile, which was true. And art, which wasn’t.

‘Then we should go and look at an exhibition.’

‘Does that count as a date?’

‘It’s what couples do,’ she’d said. ‘It’ll help us get to know each other.’

‘I thought we’d go for dinner. Or a drink.’

‘On the first date it’s best if there’s daylight. And no alcohol.’

They left the coffee shop and walked down to the art gallery, a converted industrial building on the regenerated riverside. Robert didn’t know why Marilyn had thought this was a good idea; she seemed as uninterested as he was. Hardly speaking, they wandered from floor to floor and room to room, moving listlessly from one artwork to another.

Eventually, they sat on a wooden bench in front of a large video projection. On the screen a man in a business suit was pushing a round rock, about three metres in diameter, up a dry slope strewn with pebbles. His clothes were getting covered in dust as he fought for traction in the dirt, but no matter how hard and how long he pushed, he didn’t seem to be getting any nearer to the top. Robert realised the footage was on a loop and got to his feet; he’d had enough. He thought Marilyn would take her cue from him, that she too was bored, but her eyes remained fixed on the struggling figure, and he sat back down.

‘It’s conceptual art,’ he said, and she looked at him. ‘It’s the idea that counts. The rock’s probably made of papier-mâché. Or polystyrene. He’s only pretending.’

‘He reminds me of my ex-husband,’ said Marilyn. ‘Neil made out he was a bloody martyr. But he wasn’t. He was a chemical engineer. I thought he’d be a better catch than someone more poetic. I got all the fitted kitchens I wanted. So I suppose I shouldn’t moan. But it got to be so boring. And then he left me when the youngest went to university. For someone who shared his interests, he said. What interests? That’s what I’d like to know.’

They got up together and stood in silence to read a large printed panel explaining the work. They turned to each other, and she wrinkled her nose.

‘I like the Impressionists,’ she said. ‘This modern stuff’s too clever for me.’

‘It’s all postmodernism now,’ he said, ‘Do you like Van Gogh?’

‘He’s alright,’ she said, looking at her watch.

*

Robert pushed and pulled the vacuum cleaner over the hall carpet. He was enjoying the thought of all the dust and dirt being sucked up from amongst the pattern of tiny flowers, as if he was a gardener tending to his blooms.

His phone rang and broke his concentration. A withheld number. He thought it was more telesales and was ready to be irritated, but it was Marilyn. He wasn’t just surprised. He was overjoyed.

‘I didn’t think it was that bad, was it?’ she said. ‘I mean, I’ve been thinking it wasn’t bad for a first date. Definitely some chemistry there. Well, I thought so. Didn’t you?’

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘It was nice.’

‘First dates are not really long enough, are they?’

‘I suppose not.’

‘Take it from me,’ she said. ‘Are you ready to take this to the next level?’

‘What’s that?’

‘Dinner date.’

‘Oh, yes.’

‘I’ve got a good feeling about us, Robert. Have you?’

‘Yes, I think I have, Marilyn.’

When she rang off, he stood in the living room and looked at the large black and white photograph of Alison over the fireplace. He loved the picture; the satin gown; her dyed blonde hair; her lips like a dark, tight bud, even though her eyes seemed glazed and unfocused.

‘That was Marilyn on the phone,’ he said. ‘I think things have been a little difficult for her. And you know how that makes people, don’t you?’

*

‘Have you got any other dates lined up?’ she said.

They were in a bar near the restaurant. She was knocking the ice and lemon around the bottom of her glass with a plastic twizzle stick.

‘No,’ he said. ‘Just you.’

She looked up at him and smiled.

‘Be a love and get me another, will you? We’ve still got time.’

‘Aren’t you drinking, then?’ she said, when he came back from the bar, with her gin and a bottle of tonic, but nothing for himself.

‘I haven’t finished this one,’ he said, and made a thing of knocking back some of his lager.

‘My husband could go for weeks without a drink,’ she said, ‘He was a pious bastard when it suited him.’

‘This beer’s too gassy,’ he said.

‘Do you want a short, then. A whisky?’ She grabbed her handbag and stood up. ‘My treat.’

‘Make it a g and t,’ he said. ‘I don’t really like whisky.’

They were late getting to the restaurant, but a waitress showed them straight to a table, and when she brought the menus, Marilyn asked her to bring a bottle of Pinot Grigio. ‘Straight away,’ she said.

Robert didn’t like the waiter. One too many buttons on his shirt were undone, and he fussed over Marilyn, asking her what ‘the beautiful signora’ would like. And he made crude gestures with an enormous pepper mill he brought to grind over her pasta. But she lapped it up.

Marilyn said she was optimistic about the future. And was thinking about joining a gym. Or a walking group. She asked if he’d heard anything about intermittent fasting. She talked as she ate and sauce dribbled onto her chin. Robert reached over to dab it off with his napkin.

‘You’re sweet,’ she said, reaching across the table and squeezing his hand. ‘You’re a real gentleman.’

They went to a second bottle of wine and after dessert she ordered a Sambucca. When it came there was a coffee bean floating in it.

‘Come on baby, light my fire,’ said the waiter, flicking a disposable lighter to set the drink alight.

Marilyn giggled and Robert smiled, pretending his attention was, like hers, drawn to the bright blue flame. But he’d hated the way the waiter had flirted with her, and told her to blow it out.

‘Already?’ she said.

‘Blow it out and make a wish. It’s meant to be lucky.’

Marilyn blew the flame out.

‘There,’ she said, squeezing his hand. ‘I made a wish.’

Marilyn was a little unsteady on her feet when they left the restaurant, and gripped Robert’s arm as they walked towards the taxi rank. At the crossing, she pushed up against him.

‘Let’s go to a hotel,’ she said. “And see if my wish will come true.’

‘We could go to my place,’ he said. ‘Or yours.’

‘Neutral territory, Robert,’ she said. ‘That’s one of the rules.’

They went to the hotel next to the station. As they walked up the steps to the entrance, Robert wondered if the receptionist would notice they had no luggage. He was ready with some story about missing the last train to somewhere. But the young woman, smart in a dark jacket and white shirt, just pushed the card machine towards him.

‘Breakfast’s from seven thirty until ten,’ she said, handing him a key card. ‘In the dining room.’ And she pointed somewhere behind him, but he wasn’t really paying attention.

Marilyn sagged against the reception desk.

‘Is there a bar?’

‘It’s closed now,’ said the receptionist. ‘No customers.’ She had a foreign accent. ‘There’s a minibar in the room. Or you can have room service.’

They started kissing in the lift. Robert liked the taste of her and slipped his hands under her coat to feel her body. Marilyn’s hand brushed against his groin.

‘Wasn’t this a good idea?’ she said.

When they got to the room Marilyn opened the mini-bar. Robert said he didn’t want a drink, that he’d had enough. But she didn’t take the hint, took out a miniature bottle of wine, unscrewed the cap and emptied it into a glass. He tried to distract her by kicking off his shoes and getting on the bed.

‘Come on and try it out,’ he said.

She put her drink on the side table and lay beside him. They kissed and Robert fumbled with the zip of her dress. Somehow, Marilyn slipped off the bed onto the floor. She started laughing as she clambered back up. He tried to kiss her again, but her head sagged against the pillow. She’d passed out.

Robert covered her with a blanket he found in the wardrobe. He couldn’t sleep and sat up against the headboard with the room lights off, watching television with the sound muted. Switching aimlessly and endlessly between channels he saw a rush of images; riots and girls dancing and men shooting guns and cars crashing and bursting into balls of orange flame. It was like a crazy dream, and he was glad Marilyn was there, lying next to him in the darkened room.

When he woke up the television was still on and a grey light showed through a gap in the curtains. On the other side of the bed the blanket had been pushed aside. Marilyn had gone. He pushed his face into her pillow and inhaled her smell.

*

Robert had screwed a dusting stick to the extension pole and set about clearing away all the cobwebs in the house. He was reaching up into a corner of the living room when his phone rang. It was Marilyn. She was crying.

‘Oh, Robert! What must you think of me?’

‘You just had a little too much to drink,’ he said.

‘I don’t actually remember what happened,’ she said.

‘Nothing to worry about.’

‘Do you think you could ever forgive me?’

‘For what?’

‘I don’t know,’ she paused for what he thought was a long time. ‘What happened in the hotel?’

‘You went to sleep, that’s all.’

‘I feel rotten,’ she said.

She started crying again. He said she should come over and have dinner and spend the night, but only if she wanted to. And there was a spare bed, anyway.

‘That’d be nice,’ she said. ‘It’s meant to be the best way of finding out what a man is like, you know, seeing his home.’

‘It’s a house,’ he said. ‘I mean it’s not a flat, or anything like that.’

*

Marilyn was a little late because, she said, the cab hadn’t come on time. She wheeled an overnight bag into the hallway, handed Robert a bottle of wine wrapped in a twist of white paper, and kissed him on the lips. He took her coat, taking a moment to wonder at how the fabric of her dress strained against her breasts and the roundness of her stomach.

Robert showed her into the living room and mixed them both a gin and tonic. For a moment, before he chinked the glasses together to get her attention, he watched her from behind as she looked up at the photograph of Alison above the fireplace.

‘It’s in the Hollywood style, as Jean Harlow. I took it myself.’

‘She was very voluptuous,’ said Marilyn.

‘I looked after her right up until the end. But she lost her appetite and wasted away.’

Marilyn was drinking too quickly. He’d expected that because he knew she couldn’t help herself. Anyway, it would be better if she got a little drunk. When he saw his own glass was nearly empty, he realised how nervous he was.

He had placed candles all around the dining room, and she said it was so romantic to dine by candlelight. His garlic prawns impressed her and she smiled at him every time he topped up her wine. The lamb was slow roasted. He carved it at the table and brought out more wine, a Sicilian red, and encouraged her to drink it.

‘You’re a good cook,’ she said.

‘I enjoy it,’ he said. ‘It’s a hobby, I suppose.’

He had made profiteroles for dessert. She made little noises of pleasure as she ate and he watched her.

‘You’ve hardly touched yours.’

‘I don’t really like sweet things. And when you’re the cook, sometimes, you know, you can’t face it.’

Later, when they were in the sitting room having coffee, she kept slumping against the back of the sofa. He was surprised; it had started to take effect much quicker than he thought.

‘I feel tired,’ she said. ‘Really tired.’

He helped her up the stairs into Alison’s room, and sat her on the queen-size bed. She was like a puppet with cut strings; arms flopping and head drooping. He lifted her face towards his, kissed her and ran his hand over the swell of her breasts. Then he undressed her and pulled a nightdress over her head. It was new, pink satin, one of Alison’s she’d never had a chance to wear.

In the morning Robert gently shook Marilyn awake. She opened her eyes and blinked. For a moment he’d been worried he had been too generous with the dose because he’d overestimated her weight. Wishful thinking, he thought. Now, of course, he would have to be more careful; he didn’t want any mistakes.

‘How are you this morning?’ he said, helping her to sit up and fussing with the pillows behind her.

‘I feel awful,’ she said, settling back. ‘Did I have too much to drink? Again?’

‘It’s just because you’re tired and anxious. Do you know why?’ She shook her head. ‘Because you haven’t been looking after yourself. All those skinny lattes and faddy diets. That’s not the sort of person you are. Trying to be someone else, well it’s just a strain, isn’t it?’

As Marilyn fumbled for her glasses, Robert put a tray with legs down on the bed in front of her.

‘What’s this?’ she said, looking at the cafetiere, the glass of orange juice, the croissant with butter and jam, the pain chocolat, another plate with two cream-filled chocolate éclairs, and a single rose in a small glass vase.

‘Breakfast,’ he said.

‘It looks wonderful.’

Robert sat on the edge of the bed to watch her eat. When she’d finished the croissant and the pain chocolat, he picked up one of the éclairs and guided it towards her lips. ‘Open wide,’ he said, pleased she opened her mouth without any further prompting. Cream squirted out onto her chin. He wiped it off with a napkin, the way he had in the restaurant, and she smiled at him before taking another bite. And another.

Robert was happy to see her reach for the second éclair of her own volition. It wouldn’t do to be pushy. He’d scooped out the original cream and mixed it with a concoction of his own, using extra sweetener to disguise the taste.

‘I hope you like this room,’ he said.

Her eyes flicked around, taking in the floral patterns on the wallpaper, the curtains, the duvet cover and the carpet. She nodded because her mouth was full.

‘I think of it as a beautiful garden. And do you know what the best thing about it is?’ She shook her head. ‘These flowers will never fade. They’ll always be in bloom.’

Marilyn smiled. To Robert she looked literally like the cat that had the cream. But perhaps it was too soon to tell her they were going to live happily ever after.

The End

What an excellent, well shaped story. I didn’t see the twist coming – very enjoyable.

LikeLike